Findings

Understanding Stakeholder Perception & Behaviour

Individuals perceptions and behaviour can show us how they react to public policies and compliance. Thus, this information can be leveraged in the strategic governance of the resource system.

We analyse stakeholders perceptions via the use of mental models and identify the differences in perceptions among fishers. We also examine behaviour among fishers with a special focus on risk in combination with luck, information and corporation. Additionally, we study the mechanisms that drive fisher demand for local community management (i.e. incomplete punishment institutions).

Mental Models and the M-Tool

Differences in Perceptions Among Stakeholders

Risk-Taking Behaviour Among Fishers: Social Information and Luck

Risk-Taking Behaviour Among Fishers: Cooperation

Demand for Incomplete Punishment Institutions

Back to Findings Summary

Mental Models and the M-Tool

Mental models are internal representations of an external system. They consist of causal beliefs about the how a system functions (Bostrom, 2017) and can be used to provide insights on a system based on stakeholders perceptions and behaviour (Forrester, 1992). Therefore, they are identified as a leverage point within psychology research for addressing sustainability challenges (Goldberg et al., 2020). Diagram drawing methods are commonly used to illicit mental models. The current software developed for this purpose has been successful in producing insights (e.g. Gray et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2017). However, the resulting mental models may be difficult to compare because respondents enter their own system variables. Moreover, these software have not been designed to asses mental models of individuals with low literacy.

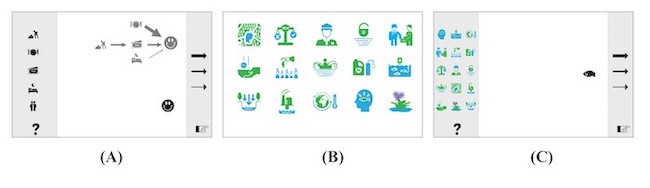

One of the key success of MultiTip has been the development of a universal tool for mental model elicitation. The Mental Model Mapping Tool or M-Tool allows participants to express their views and perceptions about causal relationships in their environment with minimal literacy and numeracy requirements (van den Broek et al., 2021a). This is due to the use of video instructions, pictograms and audio descriptions. In this tool, researchers provide participants with a set of system variables to construct their mental model which eases mental model comparability. Once the researcher has constructed the model, they can share the created study with participants via a link on the web-based app or setting it up on a tablet via the application. A CSV file of the data can be downloaded and read by analysis software such as R. The tool also captures the time that participants take to create their mental model which can be informative of the mapping process (LaMere et al., 2020). The web-based application has additional benefits such as allowing researchers to link the data to an external survey and a bar chart drawing task that displays participants views on the relation between two variables, e.g. fluctuation of a resource over time.

Screenshots of M-Tool: (A) practice session on how to create a mental model (B) presentation of the pictograms and (C) the mental model mapping screen

The M-Tool software can be downloaded for free in the App store and Google Play Store and a web-based application can be found on www.m-tool.org. The tool was developed by Heidelberg University, TAFIRI and Lambdaforge as part of the MultiTip project. It has already been downloaded over 1000 times.

We also tested the M-tool’s application in two field studies with fishers in Tanzania (van den Broek et al., 2021b). We first compared the M-tool to an alternative elicitation technique that is also appropriate for measuring mental models among participants with low literacy: semi-structure, face-to-face interviews (Findlater et al, 2018). Despite similar model composition across the two methods, we found that M-tool mental models were significantly more complex than interview mental models in the total number of drivers that participants used. Second, we related the M-tool models to participants level of education. The higher the participants level of education, the more complex the mental model the participant creates (Levy et al., 2018; Varela et al., 2020). Our study confirmed this and thus, the M-tool is validated in this context. These findings suggest that the M-Tool can successfully capture mental models among diverse participants.

To read about the policy insights and implications of these findings click here.

Researchers: Dr. Karlijn van den Broek, Dr. Sina Klein, Dr. Helen Fisher

Partners: Dr. Jan van den Broek, Joseph Luomba (TAFIRI), Lambdaforge

Publications:

van den Broek, K. L., Klein, S. A., Luomba, J., & Fischer, H. (2021a). Introducing M‐Tool: A standardised and inclusive mental model mapping tool. System Dynamics Review, 37(4), 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1698

van den Broek, K. L., Luomba, J., van den Broek, J., & Fischer, H. (2021b). Evaluating the Application of the Mental Model Mapping Tool (M-Tool). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 761882. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.761882

Top of page

Differences in Perceptions Among Stakeholders

Stakeholders’ interactions with environmental resources are strongly influenced by their mental models of the resource. Mental model elicitation can help identify disparities in perceptions between stakeholders. Individual differences in such mental models are particularly important to identify as diverse mental models may be associated with different behaviour or policy preferences and affect collaborative conservation efforts (Rouwette, 2016). During the preparatory phase of MultiTip, we explored the mental models of Nile perch fish stock among stakeholders at Lake Victoria (van den Broek, 2018). The stakeholders consisted of 76 participants from 33 different institutions (including governmental, NGO’s, business organisations, research institutions and community groups) in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. This analysis revealed large differences in the perceptions among stakeholders about the state of the Nile perch stocks and drivers of changes to the stock. These differences in perception are important as they may hinder management of the SES. In our following studies, we looked at what may influence these structural differences.

First, we looked at the structural differences in perceptions based on the type of knowledge acquisition, i.e. if the participant received knowledge of the system formally or informally (Klein at al., 2021). We conducted a survey on 225 participants across Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya and found that most participants agreed that the stock has declined. However, participants with informally acquired knowledge focused on examples of fewer drivers related to tangible human activities (e.g., the use of illegal fishing gear), whilst participants with formally acquired knowledge used more abstract and a larger variety of drivers related to the presence of humans (e.g., overpopulation).

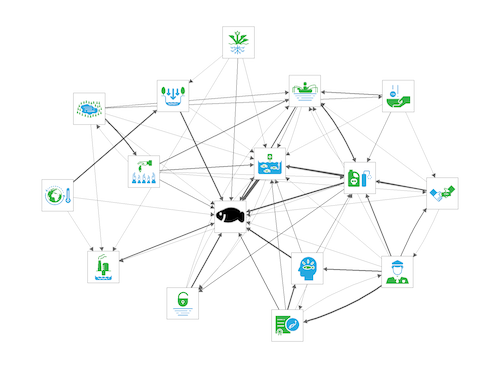

The aggregate mental model of Tanzanian fishers of the drivers of the Nile perch stock. The image shows how fishers’ mental models focus on fishing in breeding grounds, the use of destructive gear and overfishing.

Next, we explore stakeholders’ mental models of a socio-ecological system and assess content and complexity differences across experience levels, migration status, and regions (van den Broek et al., under review). We mapped the mental model of drivers of the Nile perch fish stock fluctuation at Lake Victoria for 185 Tanzanian fishers. The findings show that (1) fishers’ mental models were complex and diverse, (2) mental models tended to focus on the use of destructive fishing activities, (3) mental model complexity, but not content, varied across regions and (4) fishing experience and migration status were not consistently related to mental model complexity or content. In particular, we found that fishers converge in their perception that fishers’ activities, especially non-compliance with regulations, contributes to stock decline in a major way. These results have important implications for environmental resource management at Lake Victoria.

To read about the policy insights and implications of these findings click here.

Researchers: Dr. Karlijn van den Broek, Dr. Helen Fisher, Dr. Sina Klein

Partners: Dr. Jan van den Broek, Joseph Luomba (TAFIRI), Horace O. Onyango (KMFRI), Bwambale Mbiling (NaFIRRI), Joyce Akumu (NaFIRRI)

Publications:

Klein, S. A., van den Broek, K. L., Luomba, J., Onyango, H. O., Mbilingi, B., & Akumu, J. (2021). How knowledge acquisition shapes system understanding in small-scale fisheries. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 2, 100018.

van den Broek, K. L. (2018). Illuminating divergence in perceptions in natural resource management: A case for the investigation of the heterogeneity in mental models. Journal of Dynamic Decision Making, 4, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.11588/jddm.2018.1.51316

van den Broek, K. L., Luomba, J., van den Broek, J., & Klein, S. (Under review). Fishers’ mental models reveal their perceived role in conserving fish stock and regional differences.

Risk-taking Behaviour Among Fishers: Social Information and Luck

Risk is an essential component of fisheries decisions, especially in a complex, potentially tipping environmental system such as Lake Victoria. Fishers make many risky decisions, e.g. how much to invest in equipment and whether to comply with regulations. In this environment, they constantly receive feedback on past decisions and also observe the decisions of other fishers. The socio-ecological system of Lake Victoria adds an important dimension of risk and uncertainty because fishers livelihoods can be threatened if the ecosystem passed a tipping point. Therefore, understanding fishers risk-taking behaviour is important when considering policies for common pool resource management.

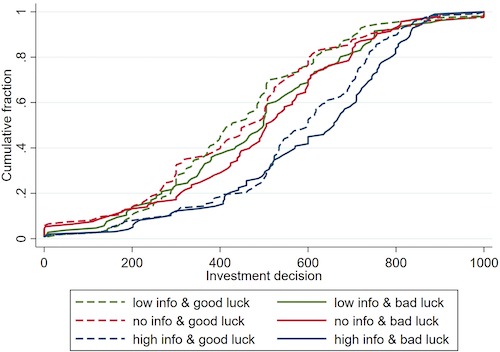

To understand how experiencing luck and social information influence fishers risk decisions, MultiTip conducted a lab-in-the-field experiment in Tanzanian at Lake Victoria (Dannenberg et al. 2022). In the experiment, fishers made a risky investment decision under controlled conditions. The experiences of good or bad luck and information about the behaviour of other fishers differed between experimental conditions. The results show that while the experience of good or bad luck does not significantly affect decision making, there are positive feedback effects between fishers. When fishers learn that other fishers engage in risky behaviour, they take more risk than fishers who get no information. However, the feedback effect is asymmetric. When fishers learn that other fishers engage in low-risk behaviour, their risk taking does not differ from fishers who get no information.

The cumulative distribution of fishers’ individual investment decisions by experience of good or bad luck and social information (no information, low information or hight information).

Note: The cumulative distribution in this graph shows the fraction of participants within the same treatment condition who invest the respective amount or less. Participants with high and low stakes in the betting task are pooled.

To read about the policy insights and implications of these findings click here.

Researchers: Prof. Dr. Astrid Dannenberg, Jun.Prof Dr. Florian Diekert, Philipp Händel (Ph.D. Candidate)

Partner: Joseph Luomba (TAFIRI)

Publication: Dannenberg, A., Diekert, F. & Händel, P. (2022) The Effects of Social Information and Luck on Risk Behavior of Small-Scale Fishers at Lake Victoria, Journal of Economic Psychology,90,102493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2022.102493

Top of page

Risk-taking Behaviour Among Fishers: Cooperation

We also examined how interactions between fishers affect risk-taking behaviour and cooperation by conducting two lab-in-the-field experiments with Ugandan fishers at Lake Victoria. In our first experiment, we examine how individual risk decisions are altered by various potential effects on another individual. Through our unique design, we are able to show whether fishers change their decisions depending on how a risky decision affects the income of another individual. We also examine which risky decisions are sanctioned by the individuals involved.

In our second experiment, fishers played a resource extraction game. In this experiment, we examine how fish scarcity changes their willingness to engage in cooperative resource management and whether fishers behave more or less cooperatively when they know that another fisher will join them later (through migrating), making him or her dependent on their prior decisions.

With the different parts of the study, we can assess how the impact of one's behaviour on others, as well as changes in environmental conditions and social structures, affect the behaviour of fishers. This will lead to a better understanding of the behavior of fishers, and the influence of their perception of the socio-ecological environment on that behavior. The results of this study will be important for understanding how best to communicate the socio-ecological situation to fishers, how to develop effective management structures and how to predict future trends in the fishery. The data analysis for this study is ongoing.

To read about the policy insights and implications of these findings click here.

Researchers: Prof. Dr. Astrid Dannenberg, Philipp Händel (Ph.D. Candidate), Sophia Charlotte Klatt (Ph.D. Candidate), Pia Fischer (Ph.D. Candidate)

Partner: Dorothy Birungi (NaFIRRI)

Demand for Incomplete Punishment Institutions

Enforcement of rules and regulations on Lake Victoria has become increasingly centralized by the national government in recent years. A frequently cited reason for this is the weak enforcement of illegal fishing activities by local institutions. Fishers, however, still prefer local enforcement by their own people to enforcement by the government (Mpomwenda et al. 2022). We conducted an online experiment with German students to understand the general mechanisms that drive demand for incomplete punishment institutions (local institutions) in a highly controlled setting.

Participants played a public goods game (6 persons) with a punishment option. Our study examines the general willingness to vote for the severity of a punishment institution that automatically punishes non-cooperative behavior of either all or a subset of players. We compare the demand for a complete punishment institution that affects all players equally with the demand for an incomplete punishment institution that affects only a subset consisting of half of the players. Since imposing a severe punishment makes it rational to contribute everything to the public good, standard economic theory predicts that rational participants would vote for a severe punishment institution if they benefit from the cooperation of the bound group. Otherwise, they would vote against punishment. To test this prediction for complete and incomplete punishment institutions, we varied the marginal group return (MGR) of the public good in different experimental treatments.

Our study shows that when the punishment institution is complete and all participants are bound to the same punishment institution, participants vote for severe punishment, as predicted by standard economic theory. However, our results also show that in the case of incomplete punishment institutions, participants choose the severity of punishment not only according to whether it is beneficial for them based on the return function, but that their decision is also influenced by other factors. Thus, the demand for incomplete punishment institutions is driven by different factors than the demand for complete punishment institutions. Drawing on behavioral economic theories, we are currently analyzing the data to better understand these other factors. This will help to better understand the general determinants of successful implementation of local (incomplete) punishment institutions as proposed by fishers.

Histogram of frequency of chosen punishment rates (severity) in different treatments divided on whether cooperation of bound group is beneficial or not and on whether the punishment institution is complete or incomplete. The treatments describe who is able to vote (one small group (3vote), both small groups (3+3vote) or all participants (6vote)) and the marginal group return of the public good for all 6 players (0.75, 1.5, 2.5).

To read about the policy insights and implications of these findings click here.

Researchers: Prof. Dr. Astrid Dannenberg, Dr. Christoph Bühren, Phillipp Händel (Ph.D. Candidate)

Top of page

References:

Bostrom, A. (2017). Mental Models and Risk Perceptions Related to Climate Change. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.303

Diekert, F., T. Goeschl, C. König-Kersting (2021): Social Risk Effects: The 'Experience of Social Risk' Factor. AWI Discussion Paper 701, Heidelberg University

Findlater, K. M., Donner, S. D., Satterfield, T., and Kandlikar, M. (2018). Integration anxiety: The cognitive isolation of climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 50, 178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.02.010

Forrester, J. W. (1992). Policies, decisions and information sources for modeling. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 42–63.

Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., & van der Linden, S. (2020). Leveraging social science to generate lasting engagement with climate change solutions. One Earth, 3(3), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.08.011

Gray, S. R. J., Gagnon, A. S., Gray, S. A., O'Dwyer, B., O'Mahony, C., Muir, D., Devoy, R. J. N., Falaleeva, M., & Gault, J. (2014). Are coastal managers detecting the problem? Assessing stakeholder perception of climate vulnerability using Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Ocean and Coastal Management, 94, 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013

LaMere, K., Mäntyniemi, S., Vanhatalo, J., & Haapasaari, P. (2020). Making the most of mental models: Advancing the methodology for mental model elicitation and documentation with expert stakeholders. Environmental Modelling and Software, 124(104589). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.104589

Levy, M. A., Lubell, M. N., and Mcroberts, N. (2018). The structure of mental models of sustainable agriculture. Nat. Sustain. 1, 413–420. doi: 10.1038/ s41893-018-0116-y

Rouwette, E. A. J. A. (2016). The impact of group model building on behaviour. In Behavioral Operational Research: Theory, Methodology and Practice, Kunc M, Malpass J, White L (eds). Palgrave MacMillan, London; 213–241.

van den Broek, K. L. (2018). Illuminating divergence in perceptions in natural resource management: A case for the investigation of the heterogeneity in mental models. Journal of Dynamic Decision Making, 4, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.11588/jddm.2018.1.51316

Varela, B., Sesto, V., and García-Rodeja, I. (2020). An investigation of secondary students’ mental models of climate change and the greenhouse effect. Res. Sci. Educ. 50, 599–624. doi: 10.1007/s11165-018-9703-1

Wood, M. D., Thorne, S., Kovacs, D., Butte, G., & Linkov, I. (2017). Mental Modeling Approach. Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6616-5

Webpage Editor:

E-Mail

Updated on:

07.11.2022